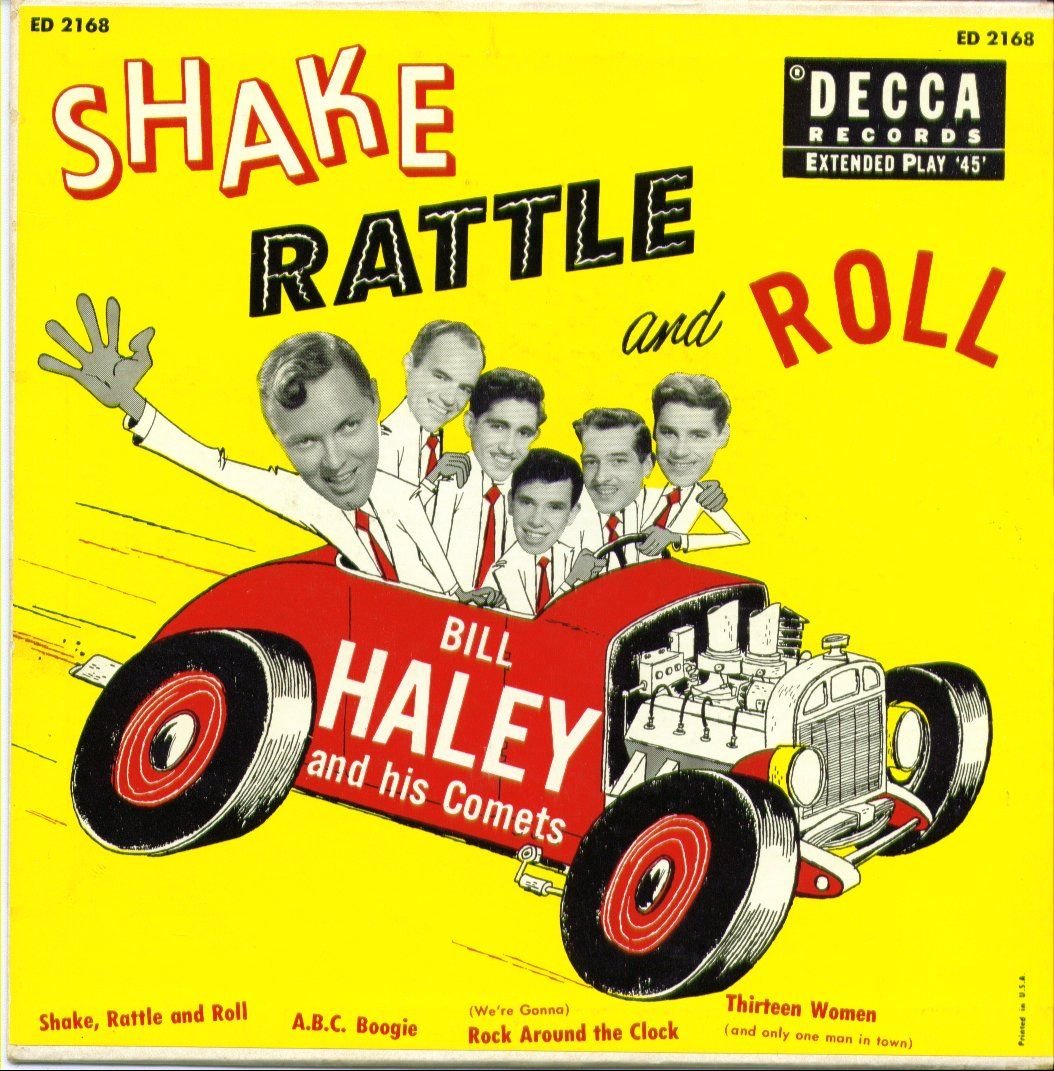

Shake, Rattle, and Roll

Parashat Vayera, Genesis 18:1–22:24

Rabbi Stuart Dauermann

If the Bible is not a book that surprises you, you are not reading it at all, not paying attention, or simply reading your own views into it.

The Bible may be the world’s most surprising book. Just when you thought you had God down, you will read something that causes even the dead to rise up and say, “What was that?”

This week’s parasha is one of those that just might shake, rattle, and roll the dead, and even some of us.

The first shaker is Avraham fudging on the identity of his wife so as not to tempt the people of the land to take her and knock him off (Gen 20:1–2). I remember discussing this with an Orthodox Jewish airliner seatmate who insisted we should congratulate the patriarch for his cleverness here. I disappointed the man by pointing out how the Torah puts words of moral rebuke into the mouth of pagan king Avimelech, shaming Avraham (Gen 20:9).

This is the second shake-rattle-and-roll in our text: the pagan king as moral arc-light. He is appalled when God tells him Sarah is Avraham’s wife, not his sister. This shaker reminds us of the Book of Jonah, where pagan sailors do everything right while the prophet of God is finding escape routes from doing the will of his Master.

The third resurrecting realization is that even though Abraham is a moral failure in this account, God still considers him a prophet. As a prophet, he has authority to pray, which, when offered, brings healing to Abimelech’s household (Gen 20:7).

What then should we make of these three shakes, rattles, and rolls?

First, we need to reconsider the sharp lines we often draw between God’s good soldiers and “the world.” These lines make for tidy thinking but have little to do with reality. Here in our story, we see the “believer,” the “good guy,” doing the bad things, and the “unbeliever”—the godless pagan—rightly perceiving the still small voice.

We all put some people groups on a pedestal while other we just put down. We make excuses for the ingroup, and make jokes about the others. Our party is the party of God and its platform written on tablets of stone with his finger. The other party has horns and a tail and smells of sulphur. For many people this is the obvious truth, but for a God who looks beyond outward appearances into the hearts of humans, it’s obviously an illusion.

This kind of categorical thinking about religion, politics, and people, is wrong. One way we know it’s wrong is that life is not like that—good people do bad things, bad people do good things, and sometimes it’s impossible to tell the bad guys from the good ones.

When it comes to biased judgments, religious people are well-known offenders, muscular in their judgments, and atrophied in their capacity to criticize themselves or their crowd.

Our parasha chastens and reminds us that sometimes you can’t tell the good guys from the bad guys without a score card, reminding us as well to make sure our score card is the same as the one in the hand of the Holy One.

Anne Lamott warned us: “You can safely assume that you've created God in your own image when it turns out that God hates all the same people you do.” And even though she’s a flaming liberal, she’s got it right, doesn’t she? Imagine that. If you can!

It’s past time to learn our lessons well.

First, we need to learn to not pile on or desert someone who fails to measure up to our image of them. They are not usually bad people. But all of us are a work in process. Let’s offer them a proper measure of support, not too much, not too little, and see what happens. If, instead, we throw stones or turn our backs on them, we sabotage their progress or miss the chance to celebrate their growth.

Yiftach was an illegitimate child whose brothers and the Gileadite elders drove out of town as just so much trash. Years later, when Gilead and all Israel were under attack by the Ammonites, these elders knew enough to send a delegation to recruit Yiftach to help them. He alone had the leadership skills to fight off the enemy (see Shoftim/Judges 11:1–11). Imagine what would have happened if they had simply persisted in writing him off!

Second, we need to learn to not idolize people, putting them on pedestals. Makers of idols are worshipers of lies. When we treat others as icons of perfection, we set ourselves up for disappointment, and them, for a fall. Again, we are all works in process, and our lives are most often two steps forward, one step back, or some variation on the theme. Let’s try to be part of other peoples’ solutions, and not their problems.

Third, we need to realize that everyone is in process. Even giants stumble. And Shorty Zacchaeus became the big guy in town (Luke 19:1–10). Holiness takes practice. Give people space. Yes, even relatives and close friends will disappoint you. But even strangers can astound you in all the best ways. Keep your eyes open, and your heart from being closed.

Avraham only expected unrighteousness from pagans, believing they would kill him to get at his beautiful wife. He was wrong. Some of us may expect nothing good from Democrats, Republicans, Liberals, Conservatives, immigrants, Palestinians, or Muslims. Let’s be careful we don’t make ourselves morally and spiritually blind and deaf.

Nothing I am saying justifies moral relativism. We must never forget this warning, “Oy to those who call evil good and good evil, who present darkness as light and light as darkness, who present bitter as sweet, and sweet as bitter!” (Isaiah 5:20). Evil should never be given the benefit of the doubt.

But neither can we justify being hard-nosed. We all need to seek and be prepared to find the grace, truth, and goodness in the discounted other. Our continual need is balance.

Pray for eyes to see the glimmer of God’s image whenever and however it appears. But don’t go through life with your eyes shut.

Wise as serpents. Harmless as doves.

Shake. Rattle. And roll.